The Special Power of Appointment Trust, or “SPOA Trust”, has been used by estate planners for many years, but only recently has it been used for asset protection. The SPOA is specifically mentioned in the trust laws of many states, as well as in the Internal Revenue Code.[1] While it has been touted as a “magic bullet” by a few planners, it is really just another tool in the toolbox, albeit an oftentimes very useful one. In other words, it is appropriate in some circumstances and inappropriate in others. However, in many instances a SPOA Trust offers unique benefits you may not achieve otherwise.

What is a SPOA Trust?

A Special Power of Appointment is often used in trusts that require special flexibility. This power is given to an “Appointer”, who has the power to give trust assets to anyone except himself, his creditors, his estate, or creditors of his estate. This power is usually used, of course, to make distributions from the trust to someone other than a beneficiary or the excluded persons we’ve just mentioned.

Why Most Domestic Trusts Do Not Protect Assets

The bane of domestic asset protection trust planning is that, in most jurisdictions a self-settled trust, by law, is not allowed to protect trust assets from the settlor’s (a.k.a. grantor’s or trustor’s) creditors. In other words, if you fund a trust in the traditional manner (by way of gift), and you wish to continue to benefit from those assets, then the trust is “self-settled” and you typically will get no asset protection. On the other hand, if you set up an irrevocable trust, and you are not a beneficiary of the trust, and do not retain improper control over trust assets,[2] then a state’s “spendthrift” laws will (subject to fraudulent transfer law) protect trust assets from most creditors.[3] By way of example, the Texas trust spendthrift statute is as follows:

“(a) A settlor may provide in the terms of the trust that the interest of a beneficiary in the income or in the principal or in both may not be voluntarily or involuntarily transferred before payment or delivery of the interest to the beneficiary by the trustee.”[4]

Although a self-settled trust will generally provide no asset protection, more than a dozen U.S. states[5] have passed Domestic Asset Protection Trust (DAPT) laws. This means that, in some circumstances, a trust may be self-settled and still protect assets from creditors. However, a DAPT typically has severe drawbacks that often make it a subpar asset protection structure. For example:

- The trust must be funded for 2 to 4 years (depending on the jurisdiction) before the protective features of the DAPT kick in. This means that after you create and fund a DAPT, if a creditor makes a claim before the 2 to 4 year period expires, then that creditor may reach assets in the DAPT. This is true even if there are no existing or foreseeable creditor threats at the time the DAPT is funded.

- A bankruptcy court may include DAPT assets in the settlor’s bankruptcy estate for up to ten years after the transfer of assets to the trust.[6]

- A judge in a non-DAPT jurisdiction will likely not respect the DAPT legislation of another state. This means that, if you set up a DAPT in another state, a non-DAPT state’s court may nonetheless allow creditors to attach DAPT assets. If DAPT assets are located in the foreign DAPT state, and you are sued in your home state, it is unclear whether the judge in the foreign state will allow a creditor to attach DAPT assets.[7]

- DAPT statutes sometimes require the hiring of a professional trust company in the state where the DAPT is domiciled. Professional trust company fees are typically, at a minimum, $1,500 per year or more.

- Depending on the situs of the trust, there may be statutory exceptions that allow certain creditors to attach DAPT assets. For example, DAPT assets may be subject to tax claims, child support, or alimony.

- One’s beneficial interest in a DAPT must typically be disclosed to judgment creditors in the course of a post-judgment debtor examination. Failure to disclose such interest is usually perjury.

SPOA Trust Advantages

The beauty of a SPOA trust is that the settlor is not a beneficiary of the trust. However, we may use the special power of appointment as a means to, if desired, give assets back to the settlor at some future point, while also making the trust non self-settled so as to obtain spendthrift protection. Unlike the DAPT, the SPOA Trust may provide meaningful protection in all 50 states.

Because a settlor of a SPOA Trust has no beneficial interest in trust assets, he retains no ownership interest in those assets. This means that he can honestly not list trust assets on a bankruptcy schedule (unless they were transferred within 1-2 years of filing bankruptcy), in a post-judgment debtor’s examination, or in a deposition. This is a benefit that very few, if any, other asset protection structures have. If you place assets in an LLC, for example, you must list your LLC interest on a bankruptcy schedule or in a debtor’s exam. The same goes for corporate stock, partnership interests, or a beneficial interest in a trust (however, unlike many other assets, a beneficial interest in a non-self-settled spendthrift trust is generally not included in one’s bankruptcy estate!)[8] We examine an important section of the U.S. bankruptcy code – section 541 (c)(2), and how it affects the SPOA trust later in this article.

Finally, one of the greatest appeals of a SPOA Trust is its simplified tax treatment. SPOA Trusts are typically set up as ‘grantor trusts’ under the Internal Revenue Code’s grantor trust tax provisions.[9] In most instances, this means we can set up the trust so that it is disregarded as being separate from its settlor for tax purposes. Trust income is treated as if it were earned directly by the settlor, and is reported on the settlor’s personal income tax return. Not having to file an extra return for the SPOA Trust thus greatly reduces administrative hassles. And, unlike an LLC, the SPOA Trust need not be publicly disclosed, and no annual reports need be filed.

Potential SPOA Trust Drawbacks

SPOA trusts do have some disadvantages. For example, like most trusts, a SPOA trust is typically funded by way of gift (however, for better protection, we may also fund it via installment sale, a strategy we discuss later). Under fraudulent transfer law, gifts are the most easily reversible type of transfer. At any point within 4 years of the transfer, or up to 7 years in a few states such as California, a judgment creditor may undo a transfer, even if the creditor was not a creditor at the time of the gift, if he can show both of the following to be true:

- The transfer was a gift, or if consideration was received, the consideration was less than fair market value; and

- The debtor is unable or unwilling to pay the creditor (insolvent).

In addition to the foregoing, if frequent distributions are made from the trust back to the settlor, a savvy creditor may argue the settlor is a de facto trust beneficiary, even if he’s not listed as such in the trust document. This may lead a judge to treat the trust as if it were self-settled. However, for a married individual with children, or for a combined trust/LLC structure (described below), it is often not difficult to structure a trust so that its assets chiefly go to the beneficiaries, e.g. the spouse and children, rather than the settlor; this is a strategy we’ll examine shortly.

Finally, we must realize that, absent a provision restricting the special power of appointment, the Appointer may distribute trust assets to anyone other than himself, his estate, his creditors, or creditors of his estate. So as to ensure an improper appointment is not made, we could appoint a trust Protector, who would have power to veto an Appointer’s actions, or even fire and replace an Appointer, or we could give the trust’s settlor the right to veto trust distributions (but not the power to replace or remove a trustee, protector, or Appointer). Note that, if the settlor retains the power to veto trust distributions, this may cause inclusion of trust assets in his estate for estate tax purposes.[10] This will not be an issue for most individuals, since currently the estate tax is only levied to the extent an estate’s assets exceed $5.25 million at the time of one’s death (or $10.5 million for a married couple).

Using a SPOA Trust with an LLC

For business assets, SPOA Trusts work best in tandem with a limited liability company (LLC). Because transfers to an LLC are an exchange of equivalent value and not a gift, a combined SPOA Trust/LLC structure (where the trust is a non-managing member of the LLC) would be less susceptible to fraudulent transfer claims, without necessarily having to make installment sales to the trust. A properly structured LLC can mitigate or even eliminate most SPOA Trust shortcomings.

For example, one could manage the LLC and keep assets inside the LLC instead of in the SPOA Trust, with the trust only owning the LLC as a non-managing member. This would mitigate concerns about whether an Appointer would always act in accordance with the settlor’s wishes. One could also receive money from the LLC by charging management fees, or by rendering services to the LLC and charging for those services. Taking out cash in this manner would prevent a creditor from arguing that the settlor is a beneficiary of the trust, since payments are for legitimate services, and are not distributions to the settlor from the trust.

Using a SPOA Trust in combination with an LLC provides more protection than using an LLC by itself. This is because, if one were to own an LLC outright, a creditor could obtain a charging order against the owner’s LLC interest. Although a creditor of an owner may not control an LLC, become a member, attach LLC assets, or force assets out of an LLC, a charging order allows a creditor to attach LLC distributions if and when they are made to the debtor-owner. If the LLC were owned by a SPOA Trust, however, then the debtor would no longer own the LLC, and the creditor could not obtain a charging order. Assuming there are no fraudulent transfer issues, a creditor would thus have no way to attach the LLC interest. He is simply out of luck!

There are instances where a SPOA Trust should not be used with an LLC. For example, case law has shown us that it is generally inappropriate for an LLC to own strictly personal assets, such as a personal residence.[11] In such an instance, we would use a SPOA trust by itself, and perhaps sell the asset to the trust instead funding it by way of gift, so as to minimize the likelihood of a fraudulent transfer claim.

Using a SPOA Trust with Family Planning to Protect Your Home and Other Property

SPOA trusts are perhaps most effective when doing planning for a married couple. This is because one spouse can place assets in trust for the benefit of the other spouse and their children (if any). So long as the settlor spouse’s assets are treated as his sole and separate property (which may require a post-nuptial or transmutation agreement, especially in community property states), then this will not be a self-settled trust. In other words, the trust will be protected against creditors of either or both spouses. This is what a court decided in Lakeside v. Evans, where a husband put a home into an irrevocable trust for the benefit of his wife.[12] The court in Lakeside ruled that, even though the husband continued to live in the house rent-free, the trust was not self-settled, nor was it the altar-ego of the husband, and the home was therefore not available to the husband’s creditors. In another case, In re Yerushami,[13] a married couple placed their home in a type of trust authorized by the Internal Revenue Code, commonly known as a Qualified Personal Residence Trust (QPRT). A QPRT is a trust where a home is placed in trust for a number of years, during which the settlors live in the property rent-free, and after which the home passes to the trust’s beneficiaries. The court in Yerushami ruled that the home was not available to the settlors’ creditors due to the fact that the settlors only retained the right to live in the home, and not ownership of the home itself. Furthermore, this type of trust was commonly used for estate planning, and therefore the transfer of the home to the trust was for estate planning purposes and not done to defraud creditors. Note that in both cases, the trusts were ‘old and cold’, i.e. they were not challenged by creditors until years after the fraudulent transfer statute of limitations had expired.

At its most basic, a SPOA trust can be used like the trust in Lakeside.

You simply have one spouse put a home or other asset in an irrevocable trust for the benefit of the other spouse – we’ll refer to this as the ‘baseline strategy’ for the rest of the article. The special power of appointment gives extra flexibility to take the home out of the trust if necessary – for example in order to refinance a home. (Note that lenders typically do not refinance a home that’s owned by an irrevocable trust, however the Garn-St. Germaine Act[14] prohibits a lender from exercising a loan’s due-on-sale clause when a home is conveyed to certain trusts, which means after refinancing, it’s acceptable to re-convey the home into the trust). A properly structured SPOA trust, or a post-nuptial agreement, also ensures that one spouse doesn’t walk away with an unfair share of marital property (as trust beneficiary) should a marriage end in divorce.

The foregoing strategy is easy to do and may very well provide meaningful protection when challenged. However, in both Lakeside and Yerushami, creditors challenged the trust because there were vulnerabilities they thought could be exploited. The defendants in both cases were fortunate that the judge chose to honor each trust, despite the substantial vulnerabilities each trust had. A different judge may very well have decided in favor of the plaintiffs. So what were these shortcomings, and how can we make a trust a strong as possible?

First, as previously discussed, gifting a home to a trust will likely result in a plan failing if it is challenged before the four year (or sometimes longer) fraudulent transfer statute of limitations expires. We may, however, mitigate this problem by selling an asset to a trust instead of funding it via gift. Any transaction that involves an exchange of equivalent value (such as a sale at fair market value) is much harder to undo under fraudulent transfer law. If an exchange of equivalent value occurs, then a creditor has to prove the transfer occurred with specific intent to hinder creditors. If the transfer occurs when the creditor seas are calm, then a future creditor will find it difficult to argue such intent, since they weren’t a threat when the transfer occurred. This is even more difficult in light of the fact that the trust has valid estate and family planning benefits, with asset protection merely as an ‘incidental’ side benefit.

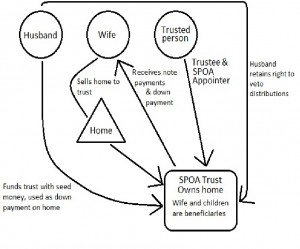

If done correctly, selling a home or other asset to a SPOA trust will not trigger tax liability, even if the asset has appreciated in value, and even if an interest-bearing installment note is involved. Figure 1 illustrates how such an arrangement would work. In Figure 1, the husband is the grantor, and the wife and children are beneficiaries (the husband and wife roles may be switched at will). The wife owns a home in her name as her sole and separate property. The husband first gifts cash or other property into the trust, equal to 10% of the home’s value (or net equity, if the home has a mortgage). This establishes the husband as the grantor of the trust. Next, the wife sells the home to the trust in exchange for an installment note. This note obligates the trust to pay for the home over several years. Installment payments may be once a year, or more often as desired. The husband’s initial funding of the trust goes to the wife as a down payment on the home, and then husband pays rent for living in the home. We structure this trust so that the wife is the owner of the trust under the grantor trust rules of the internal revenue code.[15] If husband and wife file joint tax returns, then there is no income tax due from making rent payments or paying interest on the note.

FIGURE 1

The strategy we’ve just described eliminates the vulnerabilities of our baseline strategy. First, the trust grantor does not have free use of trust assets, as he pays rent for living in the home (which payments are then used to pay off the installment note). This makes it so that he will not be seen as a trust beneficiary, which means the trust will not be deemed self-settled. Furthermore, gifts to the trust are used to make note payments (or an initial down payment to purchase the home or other property), and the property itself is sold to the trust. This means there are effectively no assets that are gifted to the trust that remain in trust. In other words, all trust assets have been sold to the trust, and it will thus be difficult for a creditor to make a fraudulent transfer claim, so long as the transfer occurred before creditor problems materialized. The installment note itself may further include anti-creditor language. The note could provide that it will cancel in the event of its involuntary assignment, or if its owner declares bankruptcy, and it could also allow for payments to be deferred for a number of years in certain circumstances.

Finally, this trust may be structured so that its assets are included in one’s taxable estate, subject to estate tax, or excluded from one’s taxable estate for estate tax savings. This highlights the fact that, in addition to structuring a trust for estate tax savings, or not, there are many other tweaks that may be made to a trust, LLC, or other asset protection plan. For example, we may set up a trust with one spouse as the settlor, another spouse as the trustee, and the children as beneficiaries, instead of using a “trusted person” as the trustee, as shown in Figure 1. Perhaps we give the special power of appointment to the beneficiary spouse, or perhaps we include no special power of appointment at all. Perhaps the arrangement in Figure 1 is used to hold property other than a home. Figure 1 is therefore only an example, and may not be appropriate for any particular individual or married couple.

Structuring a trust for stronger protection, like we did in Figure 1, makes the arrangement more complex than our initial ‘baseline’ strategy. The question anyone structuring such a trust must ask is: is the extra complexity worth it? Let’s examine how much maintenance is involved with the strategy in Figure 1. After setup, the grantor will have to make rent payments to the trust at least once per year, and the trust will turn around and make installment note payments at least once a year. In most instances, however, the trust will not have to file a tax return, and no tax liability is triggered with this arrangement. If an individual is willing to follow these additional requirements, then the stronger method should be implemented instead of the baseline strategy. However, if a person wants a very simple arrangement, then the baseline strategy provides much more protection than doing nothing.

The Offshore SPOA Trust

Due to the marketing efforts of certain asset protection professionals, the offshore trust is sometimes viewed in a negative light. However, it is viewed negatively for all the wrong reasons. You see, U.S. courts do not take issue with offshore trusts. Rather, they take issue with self-settled trusts, since U.S. laws generally do not allow self-settled trusts to protect assets from creditors. Because most offshore asset protection trusts are self-settled, they are in conflict with U.S. law and hence the stigma. But it is not the offshore aspect of the trust that is a problem, only the self-settled aspect.

The SPOA trust is designed to not be self-settled, and therefore it is compliant with U.S. law. Merely moving the trust offshore does not cause the conflict, but it may very well provide stronger protection and extra benefits. The fact of the matter is offshore trusts sometimes work, even if they’re self-settled, because when assets are moved offshore, they are moved outside the reach of U.S. courts. This was amply demonstrated in the case U.S. v. Arline Grant, where the U.S. federal government failed to bust an offshore trust in an attempt to collect on a $36 million federal debt, and where the trust’s grantor was not held in contempt of court for failing to repatriate trust assets. By using a much stronger trust, such as a SPOA trust, we may combine the extra benefits of offshore protection with the benefits of the SPOA trust. In effect, we would create the ultimate offshore trust – one that is actually compliant with U.S. law. We may also place language in a domestic SPOA trust so that it may re-domicile offshore upon the occurrence of certain contingencies, or if the trustee or another individual (such as the protector, whom we discuss shortly) deem such to be expedient. Having a trust move offshore means that, if a court assigned an installment note to a creditor, and said the note cannot cancel, then the offshore trust would simply ignore the court’s order to make note payments to the creditor instead of the trust’s beneficiary.

The SPOA Trust and Bankruptcy

Unlike with an LLC, DAPT, or other asset protection strategy, property in a properly structured SPOA trust will typically survive bankruptcy without losing ownership of trust property. This is because of section 541(c)(2) of the bankruptcy code, which states:

Section 541(c)(2) :

“A restriction on the transfer of a beneficial interest of the debtor in a trust that is enforceable under applicable non-bankruptcy law is enforceable in a case under this title.”

In layman’s terms, this means that an irrevocable, non-self-settled spendthrift trust (such as a SPOA trust) will not be available to one’s creditors in bankruptcy. Compare this to the DAPT, which the bankruptcy code specifically includes in one’s bankruptcy estate, forfeit to creditors, unless assets have been in the DAPT for at least ten years.[16] With LLC ownership, bankruptcy law is murky – an LLC ownership interest that is tied to ‘executory obligations’ may be protected in bankruptcy, however the case law is not entirely decided with regards to this matter, and therefore even a well-structured LLC interest may be at risk in bankruptcy.

Using a Trust Protector

A trust protector is an individual who has no power over trust property, but who may replace a trustee at will, or veto certain trustee actions. Essentially, a protector makes sure the trustee does his job properly, and may replace him if he doesn’t. The protector’s duties and powers are set forth in the trust agreement.

If a protector is appointed, then protector language should be carefully drafted, so that the Protector can take the trust offshore, but language would ideally not reflect that this would automatically happen in the event of creditor attack. In other words, we give the Protector the power to do this unquestionably, but without being too specific. Drafting the trust in this manner allows the grantor to claim that the protector did this on his own, and that such was not the grantor’s intent. This helps the grantor keep his hands clean should the protector move the trust offshore in order to reinforce the asset protection characteristics of the trust.

Additional SPOA Trust Strategies

Although we’ve outlined SPOA trust strategies for family planning, a single person with no children may also take advantage of the SPOA trust. In this instance, one may put an LLC in a SPOA trust, with a charity as the trust’s beneficiary. Assets will be taken out of the LLC as payments to the manager, but at portion could be distributed to the charity from time to time, with the charity receiving the remainder when the grantor dies. If that person later marries – no problem! The trust may specify that if the grantor marries or has children, then those individuals will become the new beneficiaries (this is will automatically happen because the trust provides for this), or simply use the special power of appointment to take the LLC interest out of the trust, and give it to the spouse or other individual.

Conclusion

Though not appropriate for all situations, a SPOA Trust is an exciting asset protection tool with unique benefits. It is often best combined with an LLC or other business entity, but occasionally it may be appropriately used by itself, so long as the settlor is aware of its potential drawbacks. Please send any comments or suggestions regarding this article to ryan@pfshield.com.

[1]See for example, Title 26 USC sec. 2041(b)(1), Calif. Probate Cd. Sec. 611(d).

[2] In some circumstances a settlor may retain very limited, narrowly defined control over certain assets of the trust. A skilled asset protection expert will know which powers may be retained without compromising the trust’s protection.

[3] Even the best trusts may not protect from IRS or possibly other federal government claims. See Bank One Ohio Trust Company, N.A. v. United States of America, 80 F.3d 173 (6th Cir. 1996). See also United States v. Rye, 550 F.2d 682, 685 (1st Cir. 1977); United States v. Dallas Nat’l Bank, 152 F.2d 582, 585 (5th Cir. 1945); First Northwestern Trust Co. of South Dakota v. Internal Revenue Service, 622 F.2d 387, 390 (8th Cir. 1980); Leuschner v. First Western Bank & Trust Co., 261 F.2d 705, 707-708 (9th Cir. 1958).

[4] Texas Prop. Cd. §112.035(a).

[5] States with DAPT legislation include Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and Wyoming. The protection offered between jurisdictions varies greatly. For a breakdown of DAPT protections and other DAPT benefits or drawbacks per each jurisdiction, see http://www.oshins.com/images/DAPT_Rankings_-_SJO_chart.pdf.

[6] Title 11 U.S.C., §548(e).

[7] See Where Should I Form My Limited Liability Entity? in “Asset Protection In Financially Unsafe Times” by Arnold S. Goldstein, PhD, and W. Ryan Fowler, p. 102.

[8] Title 11 U.S.C., §541(c)(2).

[9] Title 26 U.S.C., §§ 670-679.

[10] See title 26 U.S.C. §§2036-2038.

[11] In re Turner, 335 B.R. 140 (Bkrpt. N.D. Cal 2005).

[12] Lakeside v. Evans, 2005 UT App 87;2005 Utah App. LEXIS 71, Case No. 20010334-CA.

[13] In re Yerushalmi, 2012 WL 5839938 (Bkrtcy.E.D.N.Y., Slip Copy, Nov. 19, 2012).

[14]Title 12 U.S.C., section 1701j-3(d).

[15]Title 26 U.S.C.. sec. 678. This is accomplished by giving certain rights of withdrawal to the beneficiary that may not be used by her creditors to attach trust assets. The settlor may also make additional gifts to the trust, if the trust needs additional funds to make note payments.

[16]Title 11 U.S.C. sec. 548(e).