In 1989, modern international asset protection began with the Cook Islands’ self-settled asset protection trust. Since then, the asset protection industry has grown exponentially. Numerous plans have been challenged in court. Some have worked, and some have failed. These cases offer valuable insight. What have we learned from them? How has planning evolved as a result? I offer a brief survey of this important topic. Please note I mostly serve U.S. clients, however much of this article also applies to other jurisdictions.

FAPT “Don’ts”: What We’ve Learned

Early Foreign Asset Protection Trusts (“FAPTs”) relied on the following argument: if a person (“settlor”) gifts assets to an irrevocable trust in an FAPT jurisdiction, and the assets and trustee are outside the jurisdiction of any court wherein a settlor or beneficiary resides, then creditors will not be able to reach said assets. This remains a sound argument, and in 2008 an FAPT even withstood the U.S. government’s all-out attempt to collect a $36 million federal debt.[1] Unfortunately, some planners have used unwise strategies that resulted in several FAPT failures, as well as some U.S.-based settlors being incarcerated for, in the courts’ eyes, deliberately ignoring a repatriation order. An analysis of these cases reveals the following “don’ts”:

- Don’t use FAPTs for assets that can’t relocate offshore once threats arise. A local court will usually disregard foreign law, apply local law (which usually prohibits self-settled spendthrift trusts), and seize any assets within its reach. [2]

- Don’t let a settlor retain control over FAPT assets or trustees (e.g. power to replace trustees, amend the trust, act as co-trustee, etc.) Furthermore, a domestic trust protector should be replaced with a foreign protector once trouble arises.

- Trust distributions within a settlor’s/beneficiary’s jurisdiction must be done carefully, especially if a repatriation order exists.[3] Ideally, a trustee would make payments directly to vendors to support living costs (mortgage, car payment, etc.) Having a settlor use lines of credit the trust pays off is also viable.

Those who violate the foregoing forget that even though a trustee and assets are outside their country, the settlor typically remains within a domestic court’s reach. Furthermore, making a “self-created impossibility” to repatriate assets, by settling an FAPT after threats materialize (even if a lawsuit has not yet been filed) is likewise risky.

The temptation to cut corners is substantial. Protector provisions notwithstanding, a settlor may resist transferring his life savings to a foreign stranger (the trustee), without retaining power to unilaterally replace the trustee or repatriate assets. Fortunately, asset protection has evolved, and the best strategies are stronger, more flexible, and much more palatable than the traditional FAPT.

The Foreign LLC

Shortly after the FAPT’s inception, jurisdictions such as Nevis began passing Foreign Limited Liability Company (FLLC) legislation. In most instances, FLLCs are superior to International Business Companies (IBCs), due to charging order protection (explained below), lower maintenance and operational hassles, and a streamlined management structure.

FLLCs are exceptional planning tools for the following reasons:

- Transfers to LLCs involve an exchange of equivalent value (LLC membership exchanged for contributed capital), which makes them more resistant to fraudulent transfer claims.

- In progressive jurisdictions, the remedy of a member’s creditors is restricted to the charging order. Essentially, a creditor has the right to LLC distributions (attributable to the debtor-member) only if and when the manager(s) make them. In many (not all) jurisdictions, a creditor cannot compel distributions, even if the debtor manages the LLC.

- Typical FLLC setup and maintenance costs are a fraction of FAPTs. Note that while Belize, the Cook Islands, and Nevis all have very strong LLC laws, Nevis has the lowest maintenance requirements, and thus it’s my preferred FLLC jurisdiction.

- While FAPTs are contrary to the laws of most jurisdictions, which do not allow a settlor’s beneficial trust interest to be protected from creditors, LLC protection is, for the most part, recognized and supported by most of these same jurisdictions.

Some claim the FLLC is superior to the FAPT. This is not true. Rather, an FLLC has different strengths and weaknesses. For example, if a debtor is the sole LLC member, or a majority member with unilateral power (per an operating agreement) to replace managers, then a domestic court could order replacement of a foreign manager with a U.S. receiver. Jurisdictions such as the Cook Islands and Nevis forbid such by law. Nonetheless, if an LLC manager resides in the U.S., then he could be held in contempt for failing to repatriate foreign assets. Of course, we could structure an FLLC so that 5% of membership is foreign, with the operating agreement requiring consent of all members to replace management. LLC management could also shift offshore once trouble arises. Yet the FLLC faces other problems. Namely, LLCs are business entities, and must be treated as such. Unlike with FAPTs, a manager should only make payments directly to members or those who provide legitimate “arm’s length” business services. It’s not appropriate for a manager to pay a debtor-member’s bills while they are under duress. This is a classic commingling/alter-ego scenario and goes against the fabric of LLC law. Such may cause serious problems if a debtor-member is subject to a charging or repatriation order in his home country, and needs cash to pay living expenses.

Combined LLC/Trust Planning

The good news is FLLC and FAPT strengths complement one another, and help mitigate each other’s weaknesses. Properly combined FAPT/FLLC structures are a big step forward, although there are still instances where either a standalone FAPT or FLLC is preferable.

The beauty of LLC/trust combined planning is that a client may often settle an FAPT and continue managing transferred assets, without committing the cardinal “retained control” sins of standalone FAPT planning. Essentially, a person settles an FAPT, and then the FAPT forms an FLLC. FAPT assets are then placed in the FLLC, and the settlor (or his associate) is appointed manager. Because the FAPT now owns an LLC interest, and has no ownership in assets it transferred to the LLC, a settlor may manage LLC assets while retaining no control over FAPT assets (the LLC membership). Not only does this allow the settlor to manage assets he otherwise ought not manage, but since the LLC is owned by the FAPT, the settlor’s creditors may not obtain a charging order against it. Furthermore, an LLC manager could make distributions to its member (the trust) without violating accepted LLC practice, and the trustee could make prudent disbursements in a manner free of local court interference.

Domestic/Foreign Hybrid “Contingency” Planning

International planning is often more costly than domestic planning. Though the strongest plans are completely foreign, a domestic/foreign hybrid plan has lower setup and maintenance costs, and is almost as protective. An effective strategy is to form an FLLC that’s owned by a domestic trust. The trust situs, LLC management, and assets would be moved offshore should a creditor “contingency” materialize. This is done independent of the settlor, thus keeping his hands clean from any perceived attempts to evade creditors. Essentially, a lower-cost domestic trust is used until the extra power of an FAPT is needed, thus resulting in a more affordable overall plan. The FAPT may even be re-domiciled onshore once creditor threats are fully resolved.

Foreign Private Placement Life Insurance (FPPLI) and Annuities

One way to supplement an FAPT is for the trustee to purchase a FPPLI policy or annuity. For policies with over $1 million paid-in premium, commissions and overhead is minimized, growth may be accessed tax-free via loans (which need not be repaid), and assets are shifted to an investment manager appointed by the insurance company. This strategy has three benefits. First, funds are often “safer” in the settlor’s eyes, since they’re now controlled by a (usually) much larger, better capitalized, and more tightly regulated insurance company. Second, a properly-structured policy helps meet the settlor’s burden of proof that it is indeed impossible to repatriate assets. Finally, the settlor now has a reason for international planning other than asset protection: tax-free investment returns and access to global markets via the policy.

The Special Power of Appointment: Must an FAPT be Self-Settled?

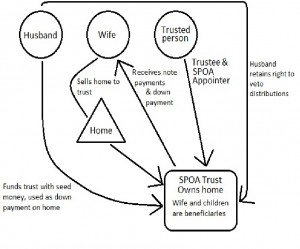

The Special Power of Appointment (“SPOA”) is an old estate planning tool that has recently been adapted for asset protection. A SPOA allows an individual, the “appointer”, to make a distribution of trust property to anyone in the world, other than the appointer, his creditors, his estate, or his estate’s creditors. As an extra safeguard, a SPOA could be subject to trustee or protector approval, or to veto by the settlor. This allows for distributions to the settlor, or to anyone who could help the settlor while under duress, without him being a trust beneficiary. The SPOA allows for a trust that is both palatable to the settlor, and protected under U.S. non-self-settled spendthrift law as well as the laws of most common-law jurisdictions.

A SPOA is not a magic bullet: repeated distributions to the settlor may lead a court to conclude the trust is actually self-settled. Nonetheless, it’s much more difficult to prove the trust is self-settled than to prove such when the settlor is a named beneficiary! Add the fact that a SPOA trust will in many instances survive U.S. bankruptcy scrutiny[4] whereas a self-settled trust will often not,[5] and considering that periodic payments could be made to the settlor for managing the FLLC, without using a SPOA (in an LLC/trust structure), and you have a plan that is strong even if it were purely U.S.-based.

Summary

The traditional self-settled FAPT, when implemented and maintained properly, remains a viable tool. Nonetheless, the best planners have taken the lessons learned since 1989 and developed new tools to make international planning more affordable, flexible, and protective than ever.

Copyright © 2015

Southpac Trust (www.southpactrust.com) in collaboration with The Privacy & Financial Shield LLC (www.pfshield.com)

[1] United States v. Raymond Grant and Arline Grant, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51332, U.S. District Ct., S.D. Florida, May 27, 2008.

[2] Brown v. Higashi (In re: Case No.A95-00200, Alaska Bankruptcy Court, 1996); Dahl v. Dahl, P.3d, 2015 UT 23, 2015 WL 404521 (Jan. 30, 2015).

[3] U.S. v. Grant, 2013 WL 1729380 (S.D.Fla., April 22, 2013).

[4] Title 11 U.S.C. § 541(c)(2).

[5] Title 11 U.S.C. § 548(e).